26. Getting Weird with Culture-Bound Syndromes

Running amok and the "sudden mass assault"

Dear Readers,

I turned fifty this year. Is that the official start of “old”? Perhaps. Though for me, at least physically, it was forty-five. Within weeks my vision started to go. Soon I was wearing “readers.” And then the aches. The pains. The insomnia.

It took me a while to adjust, but I think I’ve gotten the hang of it. I’ve learned that the real key to growing old gracefully is to simply talk less. Just STFU, as the kids say. Whatever you’re itching to say is probably inappropriate for some reason you don’t understand. So keep it to yourself, grandpa!

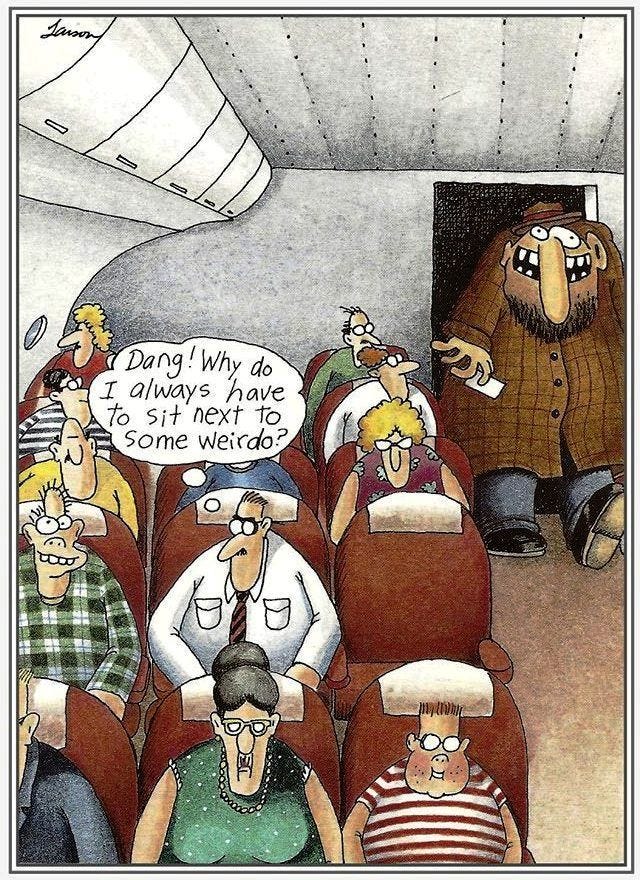

Not that I’m afraid of being “weird.” Weird is cool. Even my twelve-year-old daughter tells me that. Weird can also be unbelievably fascinating, especially when viewed at arm’s length rather than, say, next to you on an airplane.

This is a long way of introducing the very weird “culture-bound syndromes”—a group of often bizarre behaviors or afflictions that are restricted to specific cultural geographies—and, specifically, the phenomenon of “running amok.” You’ve heard the phrase, but it has a longer and more fascinating history than you likely realize. Not only was it routinely used to describe crazed “marihuanos” in Mexico, but its origins lie in a remarkable culture-bound syndrome that deeply complicates our ongoing inquiry into the history of marijuana and marijuana “fiends” in North America.

Historically the phrase “run amok” has been used to describe a very real psycho-cultural phenomenon indigenous to the Malay Archipelago and nearby territories. First noted by Western observers during the Age of Exploration, “amok” continues to garner the attention of twenty-first-century medical anthropologists. And, intriguingly, it looks just like the marijuana rampages of early-twentieth-century Mexico.

It is, in fact, a phenomenon that has sometimes been associated with psychoactive drug use. In the late eighteenth century, for example, a British travel writer and businessman named John Henry Grose noted that in Surat, India cannabis drugs sometimes produced the following effect:

A temporary madness, that in some, when designedly taken for that purpose, ends in running what they call a-muck, furiously killing every one they meet, without distinction, until [they] themselves are knocked on the head, like mad dogs.

If that sounds eerily similar to the 1913 New Year’s Day incident in Ciudad Juárez, it should. But “amok” is a lot more interesting than even that.

Recent scholarship has defined amok as “a sudden mass assault,” where an individual, after a period of brooding, attacks those around him or her in an outpouring of more or less random violence. This is generally followed by claims of amnesia on the part of the individual.

Amok is perhaps the most famous of the culture-bound syndromes. There is considerable debate over whether such behaviors should be classified as psychiatric disorders or as “socially learned, culturally channeled and sanctioned means of expressing normally forbidden emotions.”

Whatever the case, the concept of amok, though indigenous to Southeast Asia, has behavioral cousins worldwide. As the scholar John Carr notes:

It has been loosely associated with cathard in Polynesia, psuedonite in the Sahara (Kiev 1972), mal de pelea in Puerto Rico (Yap 1969), wihtiko among the Cree Indians, 'jumping Frenchmen' in Canada, imu in Japan (Cooper 1934), mirachit in Siberia (Lin 1953), pibloktoq among polar Eskimos (Kloss 1923), 'frenzied anxiety state' in Kenya (Carother 1948), 'wild man behavior' in New Guinea (Newman 1964), and finally, 'Whitman syndrome' in the United States (Teoh 1972).

I know what you’re thinking. What the hell is “jumping Frenchmen”?!? I have to admit that I DON’T KNOW, though I promise to investigate this further.

But the last one—Whitman Syndrome—should be especially interesting for those of us living in the twenty-first-century United States. Whitman Syndrome is named after Charles Whitman, the ex-Marine sniper who in 1966 murdered his wife and mother and then climbed to the top of the University of Texas clock tower and began randomly shooting people for more than ninety minutes, killing eleven.

He is the original and prototypical American mass shooter. Some scholars have compared his rampage to classic amok behavior, including it in a category of culture-bound syndromes known as the “sudden-mass-assault taxon.”

In short, as we consider whether the Ciudad Juárez rampage could actually have been caused by marijuana, we must reckon with amok and other culture-bound syndromes. And that reckoning will lead us down a few different roads. After all, amok has sometimes been tied to drug use, including cannabis. Yet amok’s history also suggests that such behaviors sometimes manifest all on their own, no drugs necessary.

It’s all pretty weird. But, you have to admit, totally fascinating. We’ll explore this further in the coming days.