21. Marijuana, Madness, and the Empress Carlota

How the wire service started bringing stories of reefer madness to the USA

Dear Readers,

A couple of weeks ago I regaled you with stories of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, his connection to “Cinco de Mayo,” and the many ways that the United States and Mexico are intertwined. But somehow I didn’t mention Maximilian’s intimate connection to the history of marijuana! And it’s intimate. I mean really intimate.

Luckily I have great friends, one of whom helped me realize that I had “buried the lede,” as the journalists like to say.

The friend in question is Will Sikes, co-owner (with his father and brothers) of Caza Sikes, an auction house here in Cincinnati. You can occasionally catch his brother Graydon on the Antiques Roadshow, a program that is regularly enjoyed here in Casa Campos by the whole family. Will also hosts a tremendous Super Bowl gathering every year at his lovely home to which I bring a hat full of prop bets and try to turn a bunch of otherwise upstanding citizens into degenerate gamblers. It’s a lot of fun.

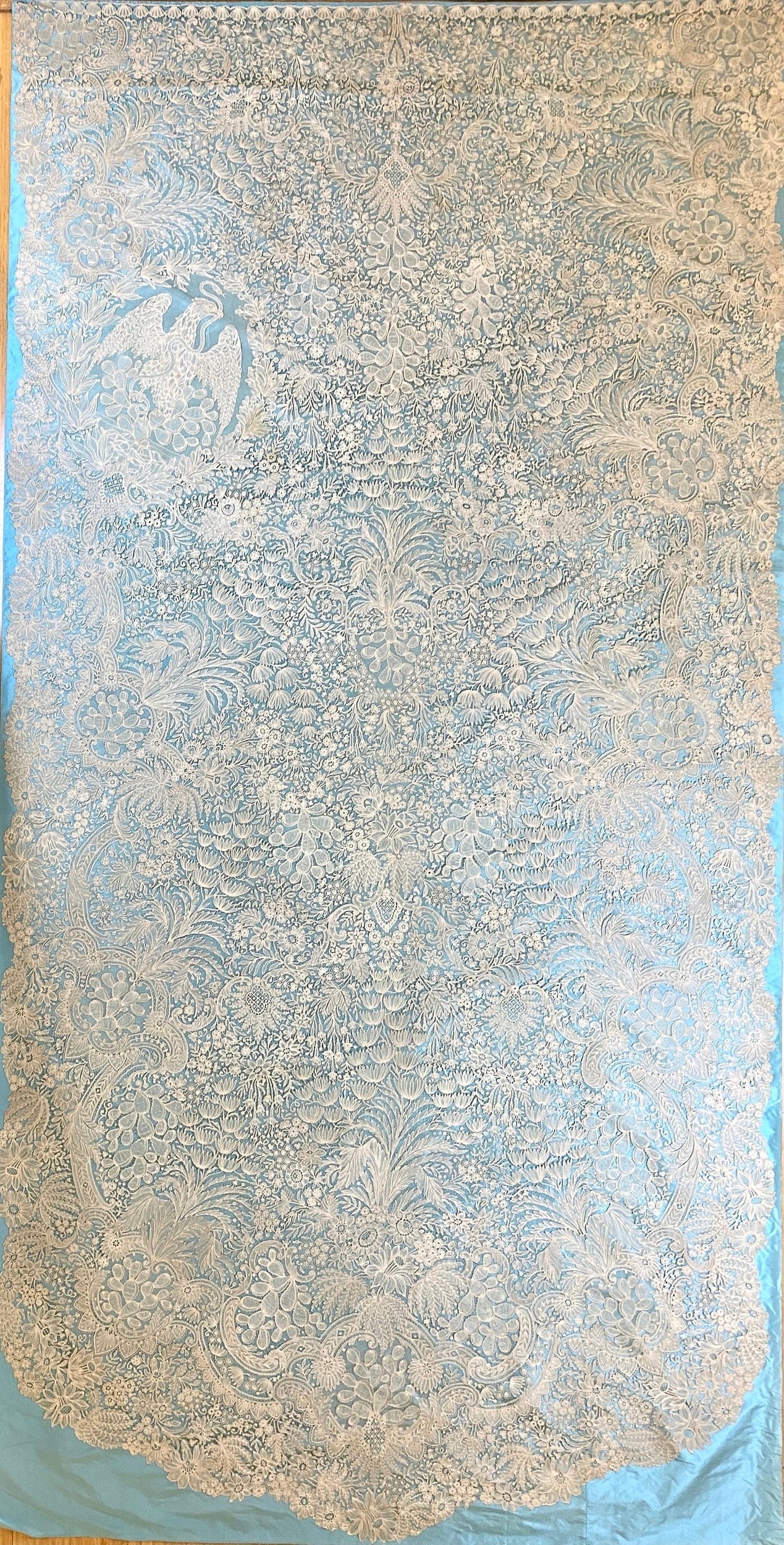

In any case, Will reached out after my post on Maximilian because Caza Sikes had recently sold the coronation veil of the Empress Carlota, also known as Charlotte of Belgium, aka, Maximilian’s wife!

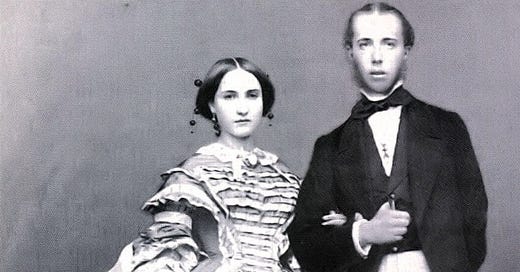

Here’s the happy couple just five years before taking over in Mexico and looking, frankly, a little too young to be running an empire all on their own:

And here’s the veil that Caza Sikes auctioned off for $24,600 last June:

So what does this have to do with marijuana? Good question!

Surely the most famous story about marijuana in late-nineteenth-century Mexico involved the unfortunate Carlota. Not only did she see her young husband sent to the “Hill of the Bells” to be executed on June 19, 1867, but she famously went mad while performing her various duties as empress. And what, you ask, caused said madness? Well, in Mexico, the classic story was that someone had slipped some marijuana (or in some versions, Datura stramonium) into her coffee, and that was that.

The Carlota story was an offshoot of a classic trope in Mexico about drugs, especially those sold by herbolarias, that is, traditional—usually indigenous—folk healers. We’ll dig much deeper into that trope at some point in the future. But, for now, the story illustrates just how wicked marijuana’s reputation was in nineteenth-century Mexico. This was a substance that was considered so potentially dangerous, and so powerful, that just a bit of it in your coffee might drive you insane! Just like poor Carlota!

And that reputation started spreading to the United States in 1895. At the center of this story is a single, small newspaper in Mexico City that was targeted at English-speaking businessmen.

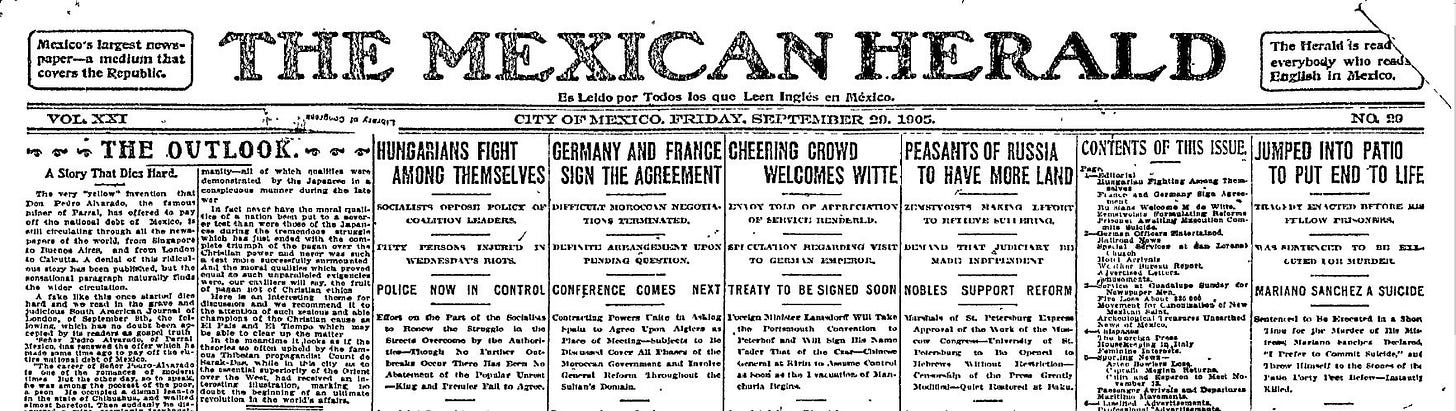

You’ll remember that the 1890s were right in the middle of Porfirio Díaz’s era of “order and progress,” during which the “gringos” were encouraged to come down Mexico way and do business. Well, most of the gringos that arrived didn’t speak a lot of Spanish, so there was a market for an English-language paper, and in 1895 that took the form of a new publication called The Mexican Herald.

The Herald published the same kinds of stories that were being published in Mexico’s Spanish-language press, and sometimes the exact same stories, but in English, making them available for the wire service to send to newspapers throughout the United States around the turn of the twentieth century. And, importantly, this was just as newspaper distribution was reaching its all-time high in the United States. By the 1910s there were nearly 2,500 dailies and 16,000 weeklies in circulation in the USA! Whoa!

As we’ve seen, since at least the 1840s, marijuana had been reputed in Mexico to cause madness and violence. By the late nineteenth century this reputation was so widespread that a student at Mexico’s National Medical School dedicated his 1886 thesis to the following question: Should marijuana users be responsible for crimes committed while under the influence of the drug? His answer: “The criminal responsibility of an individual in a state of acute marijuana intoxication should be exactly the same as that of the maniac.” That is, none.

Meanwhile, the Mexican press routinely published reports of marijuana maniacs running loose in the streets, and beginning in 1895, the Mexican Herald began delivering such stories to Americans via the wire service.

For example, in 1898, Salt Lake City’s Broad Axe picked up this story from the Herald:

The evil of marihuana smoking appears to increase rather than diminish among the lower classes, but the most alarming feature in connection with this course is the growing use of the maddening weed by the young. An illustration of this was given yesterday afternoon in the Calle de las Damas, where a young boy not much over twelve years of age, who had been crazed by smoking marihuana, was running wildly down the center of the thoroughfare, tearing his clothes and attacking all who crossed his path.

This same marijuana story appeared in the Lamar, Colorado Register, the Dolores, Colorado Silver Star, and the Saratoga, Wyoming Sun, among surely many other publications nationwide.

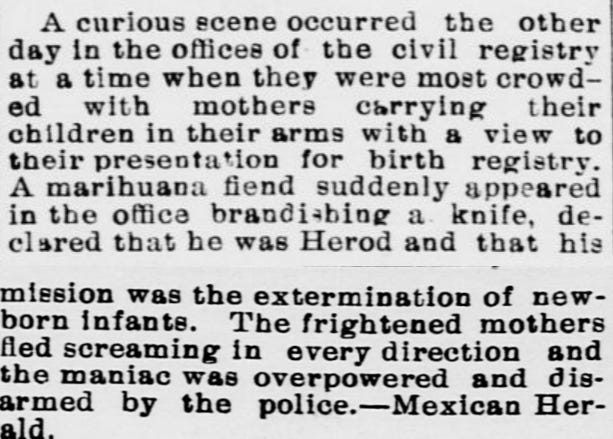

The next year, the El Paso Daily Herald published this gem from The Mexican Herald:

And so forth.

These kinds of stories were distributed nationwide and gave Americans their first introduction to “marihuana” ( or “mariguana”), a supposedly new (at least to American audiences) Mexican drug.

Gradually people started to realize that this “new drug” was actually the same cannabis that had been written about so often already in the United States, the source of “oriental dreams” and so on. But the stories filtering in from Mexico were beginning to make the cannabis “brand” decidedly more sinister.

So where did those tales of wild Mexican marijuana fiends come from in the first place? We’ll start exploring that question over the coming days. For now, enjoy some Patsy Cline singing of young love and precious veils south of the border. And have a good weekend.

Great article! Caza Sikes to the rescue again! Love the Patsy Cline closing song too. Reminds me how Mad Men episodes used to close out.