Dear Readers,

Last time we learned about psychedelic chocolate bars and the key concept of “drug, set, and setting.” Today we’re continuing our exploration into nineteenth-century cannabis use and, specifically, why recreational cannabis took so long to catch on in the United States.

Again, I suspect this had much to do with nineteenth-century Americans using unpredictable edible cannabis preparations and getting WAY TOO STONED. Sometimes this would result in wonderful symptoms that the artisans at “Perfect Dose” would surely categorize as “therapeutic” or even “religious.” But sometimes the result was something else altogether.

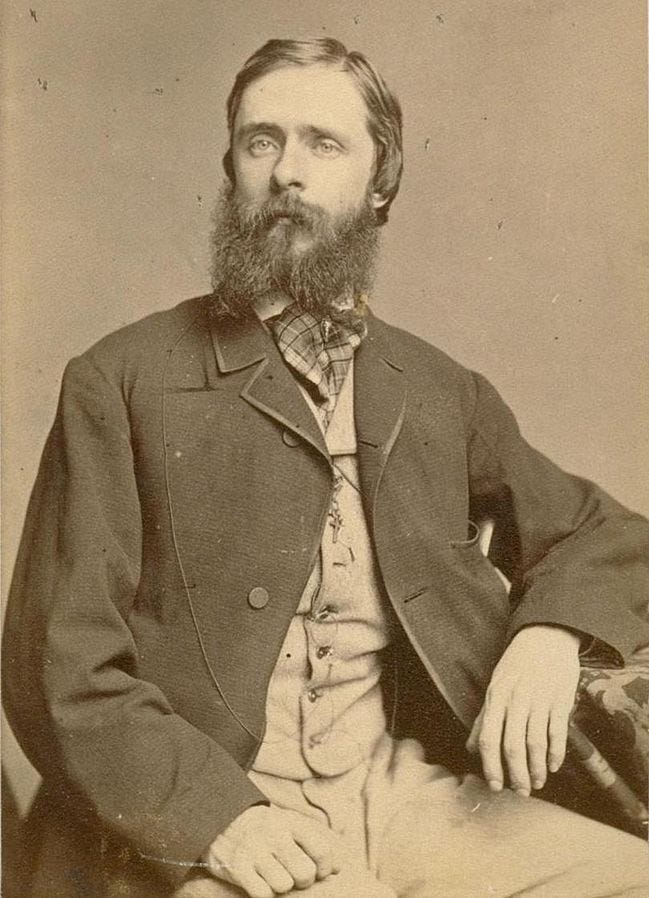

Consider the nineteenth century’s most famous American chronicler of cannabis intoxication, the writer and adventurer Fitz Hugh Ludlow, who in 1857 published The Hasheesh Eater.

The dashing Ludlow was following in the footsteps of various nineteenth-century writers in committing his experience with drugs to print. The most famous of these was surely Thomas De Quincey, whose Confessions of an Opium Eater (1821) described his own gradual descent into opium addiction and its impact on his writing. De Quincey’s book was a sensation and there would eventually be a lot of imitators, including Ludlow. Indeed, I suspect that Ludlow decided to swallow his drugs because that’s how De Quincey and other European drug experimenters of the first half of the nineteenth century did it. He certainly knew that cannabis could be smoked: “The dried plant is smoked in pipes or chewed, as tobacco among ourselves.”

But he decided to swallow it, and his reported experiences ranged from marvelous to terrifying. For example:

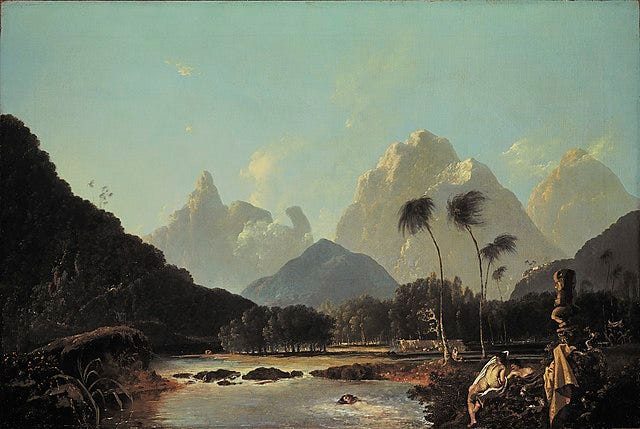

I existed by turns in different places and various states of being. Now I swept my gondola through the moonlit lagoons of Venice. Now Alp on Alp towered above my view, and the glory of the coming sun flashed purple light upon the topmost icy pinnacle. Now in the primeval silence of some unexplored tropical forest I spread my feathery leaves, a giant fern, and swayed and nodded in the spice-gales over a river whose waves at once sent up clouds of music and perfume.

Whoa!

And it wasn’t just Ludlow. Many such descriptions were published in a variety of sources, from medical journals to newspapers. Some of these also drew on the experiences of key French literary figures—the “Club des Hashishins”—and their writings about cannabis. An 1849 piece in the Louisville Examiner, for example, described Theodore Gautier’s remarkable hashish experience during which he saw “millions of butterflies, confusedly luminous, shaking their wings like fans.”

Never did similar bliss overwhelm him with its waves: he was lost in a wilderness of sweets: he was not himself; he was relieved from consciousness, that feeling which always pervades the mind; and for the first time he comprehended what might be the state of existence of elementary beings, of angels, of souls separated from the body: all his system seemed infected with the fantastic coloring in which he was plunged.

Sign me up! As an Alabama newspaper explained about hashish in 1852, “if the accounts of its effects be not exaggerated, it is strange that it has not come more in use among the western nations.”

And that is precisely my point. These were virtual advertisements for cannabis use. It’s a lot to ask someone to “just say no” to comprehending that “state of existence of elementary beings, of angels, of souls separated from the body.” Though hold on . . . just receiving a text from Perfect Dose now . . . they say that would be precisely 12-14 pieces of their chocolate!!

I kid, of course. That would be absurd. As we learned last time, results will always vary depending on “set and setting,” and these writers definitely had a particular “set” before they flew off on these psychic adventures. They were “Orientalists” in search of “Artificial Paradises,” and they often found them. But they also often got more than that in the bargain. Ludlow described numerous terrible experiences with hashish, and he attributed this to his inability to dial in the perfect dose, as it were: “So exceedingly variable are its results, that, long before I abandoned the indulgence, I took each successive bolus with the consciousness that I was daring an uncertainty as tremendous as the equipoise between hell and heaven.”

I do not know how long a time had passed since midnight, when I awoke suddenly to find myself in a realm of the most perfect clarity of view, yet terrible with an infinitude of demoniac shadows . . . . Beside my bed in the centre of the room stood a bier, from whose corners drooped the folds of a heavy pall; outstretched upon it lay in state a most fearful corpse, whose livid face was distorted with the pangs of assassination.

Now that doesn’t sound so great. It reminds me of seeing ZZ Top (beards, spinning guitars, etc.) on mushrooms c. 1992. Highly disturbing.

And that is my second major point: while there were some positive descriptions of cannabis effects, there were at least as many terrifying ones that would’ve warned ordinary people off of cannabis drugs. And these stories got around.

Even back in those days every town, large or small, had a newspaper, and these were vectors for the spread of Ludlow-style drug stories. For example, the following appeared in 1869 in the Marshall County Republican of Plymouth, Indiana (pop. 2,500), written by a doctor who claimed to have “often” taken hashish in the name of science. Me too! Always in the name of science!

He described an intoxication that began with a disagreeable “contraction of the nerves of the throat,” and which led to his senses becoming extraordinarily acute and his experiencing bizarre hallucinations and suggestiveness:

I recollect on one occasion being persuaded that my leg was revolving upon its knee as an axis and could distinctly feel as well as hear it strike against and pass through the shoulder during each revolution. Any one may make you suffer agony by simply remarking that a particular limb must be in great pain, and you catch at every hint thrown out to you, nurse it and cherish it with a morbid eagerness that savors strongly of insanity. This state is a very dangerous one, especially to a novice: madness and catalepsy being by no means uncommon terminations to it.

As with Ludlow’s book, often the pleasant and unpleasant appeared in the same source. While some of this surely had to do with this emerging “I totally just freaked out on drugs” genre and its standard conventions, I strongly suspect that it was also influenced by the consumption of highly unpredictable edible doses of cannabis. Ludlow in fact said as much: “I have taken at one time a pill of thirty grains, which hardly gave a perceptible phenomenon, and at another, when my dose had been but half that quantity, I have suffered the agonies of a martyr, or rejoiced in a perfect phrensy.”

Why didn’t they just take a consistent dose, you ask? Well because, as noted last time, no one understood how cannabis produced its psychoactive effects. Cannabinoids weren’t discovered until the 1960s. And cannabinoids are complicated, and break down over time, and vary enormously from one cannabis strain to another. And thus, while there were some high-profile cannabis experimenters in the nineteenth century, more generalized recreational use would not catch on in the United States for several more decades.

But this is just one piece of the puzzle. Next week we’ll consider a few others. In the meantime, I hope you have a safe and relaxing weekend.

To the good Dr. Campos - love the article, love the series so far. This point of yours, that these hash eaters were getting "WAY TOO STONED." begs a question (not needing an answer from you of course, you're a busy thinker I'm sure) -- how are you perhaps defining that boundary (and what it means to go beyond?) What exactly is way to stoned? Don't get me wrong, they obviously were having a lot of mixed highs/trips, whatever, as they did their orientalist thing. But I wonder whether it truly is the case that these explorers of the mind would agree that they were "way too stoned?" It seems like they were purposefully engineering their set and setting to have this big grand experiences of intoxication... it's just that sometimes they had a bad go of things and see corpses etc, and sometimes, things were all unicorns and rainbows... and they were pretty objective in bookending the highs and lows of the experience spectrum (be it surely sensationalized.) So I don't know... "Way too stoned" is really a subjective call... or further begs "Way to stoned" to do what exactly? Not meaning to cast dispersions on your work, it's great, but seems like a lot of those people were trying to alter their view of the world in this experimentation and that's always a roll of the dice... or so I've heard... Well done, keep up the good work.